Research Areas

Structure, physiology, and function of rare primate ganglion cells

The ability to functionally classify ganglion cells in the living eye, then return to study the same cells in subsequent experiments forms the foundation of the lab's research. We can currently distinguish over 20 distinct functional classes based on their contrast, spectral, spatial and temporal tuning. The ongoing effort to improve classification stimuli and analyses allows us to continue learning new things about foveal ganglion cells and often reveals exciting new research directions. We are also interested in utilizing connectomics to determine the underlying circuitry responsible for the exciting new response properties identified with calcium imaging.

Our ultimate goal is to identify the very best stimuli for each ganglion cells type, ones that get at the heart of each neuron's role in vision. Potential projects in this area focus on specific cell types (e.g., ON direction-selective ganglion cells) or population coding of specific visual features (e.g., visual signals created by eye movements).

Ganglion cell degeneration in cortical blindness, retinal contributions to blindsight

V1 damage is common in strokes and leads to cortical blindness, a complete loss of conscious visual perception in the affected area. However, some visual capabilities are preserved (blindsight); patients can detect orientation, make reflexive eye movements, and even adjust grasp while reaching for objects -- all without conscious visual awareness. Remarkably, this apparent boundary between conscious and subconscious vision is not fixed, as training developed by our collaborator Dr. Krystel Huxlin can restore some visual awareness and performance.

Cortical blindness also offers a rare opportunity to isolate the contributions of rarer ganglion cell types and their contributions to subconscious visual functions. V1 damage leads to retrograde degeneration, beginning in the LGN and that eliminates ~80% of RGCS, particularly the midget RGCs, while maintaining the rarer RGC types. Little is known about how ganglion cell physiology changes prior to cell death and how the response properties of the resilient types are altered. This work is important for identifying when early treatment might be effective in stroke patients.

Using an animal model of V1 damage, we are interested in the following areas:

- Longitudinal monitoring of the changes in physiology that occur in midget ganglion cells during degeneration.

- Physiology aimed at linking the response properties of resilient rarer ganglion cell types to blindsight.

- Connectomic reconstruction of remaining retinal circuits to determine how the retina remodels and rewires in the absence of the most common ganglion cell type.

Linking rare retinal ganglion cells to downstream visual functions

A common theme in the research areas above is the goal of placing primate ganglion cells in the context of the visual functions they evolved to mediate. The value of performing our physiology experiments in the living eye is that we can design follow-up experiments to test any hypotheses that arise regarding their roles in vision. We plan to develop a platform for performing causal loss-of-function manipulations that will allow us to test the necessity of specific ganglion cell types for downstream visual functions. A better understanding of the division of labor between the retina and the brain will be critical for developing retinal prosthetics and other vision restoration strategies.

Techniques

We are guided by research questions and use whichever technique is most applicable to a given research question. Fortunately, we have excellent colleagues and collaborators both within and beyond the University of Rochester. The main tools of the lab are functional imaging with adaptive optics, connectomics, circuit tracing and computational modeling. We focus on non-human primates (macaque and marmoset) to ensure our findings can directly translate to efforts to understand, diagnose, treat and restore vision in humans.

Adaptive Optics

Critical to our work is the ability to non-invasively study retinal structure and function in the living eye with adaptive optics. This approach enables longitudinal imaging of the same retinal neurons for months or years. This provides unique opportunities to study the response properties of retinal ganglion cells in their natural habitat (the living eye), track the progression of retinal degeneration, and to establish direct links between ganglion cell function and behavior.

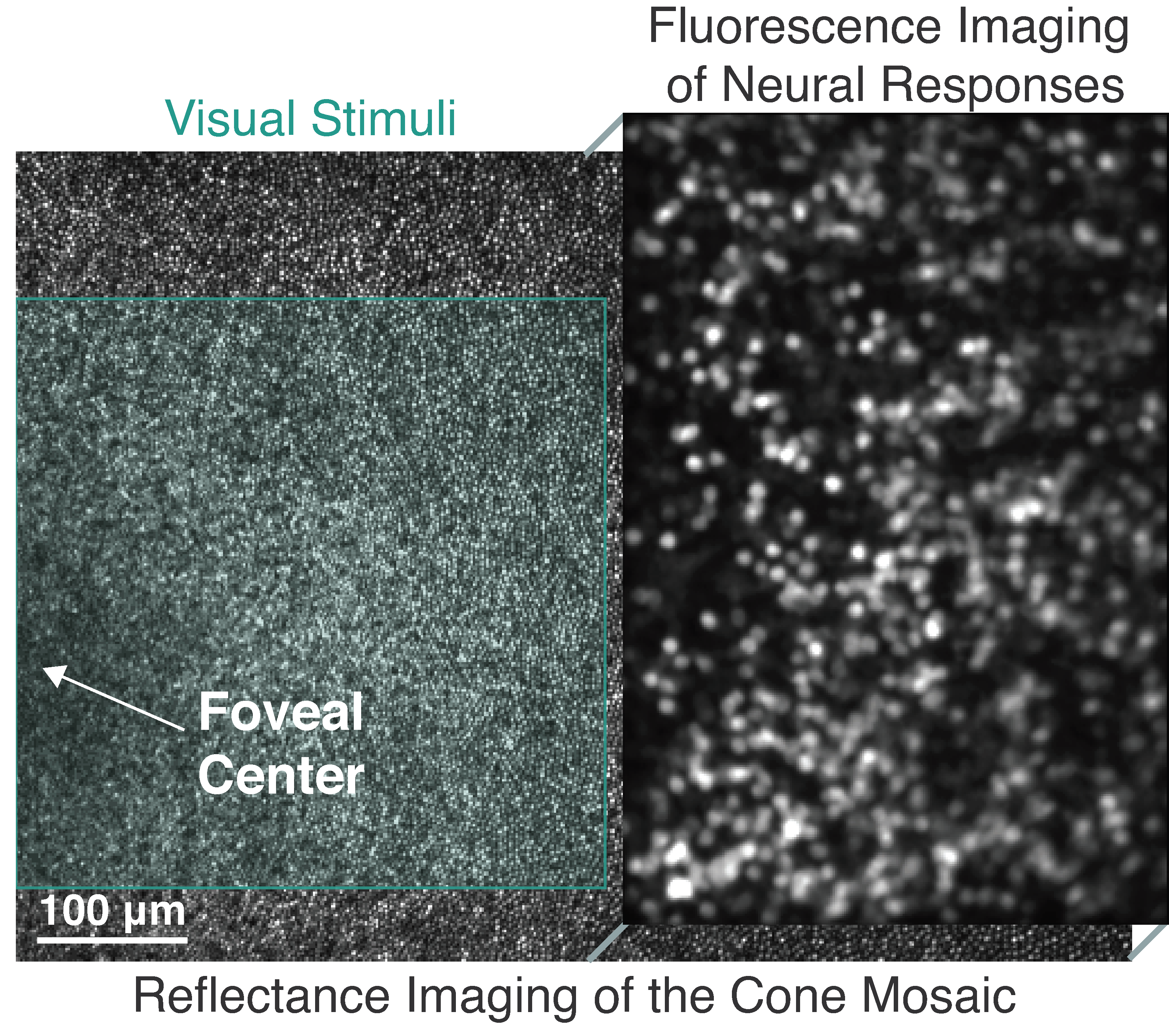

We use a fluorescence adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope, which is essentially a confocal microscope with the added capability of detecting and correcting for the eye's aberrations in real time. Viral vector-mediated gene delivery is used to express genetically encoded calcium indicators in the ganglion cell layer, which allows us to monitor the activity of hundreds of ganglion cells simultaneously while presenting visual stimuli.

Functional retinal imaging with adaptive optics is still a relatively new technique and there are also many opportunities to make substantial technical advances for students who are interested in optics, engineering, or computer science. For example, we plan to implement high-speed imaging strategies to improve the temporal bandwidth of calcium imaging and detect action potentials with voltage imaging.

Non-invasive functional imaging of foveal ganglion cells in the living macaque eye. Due to the fovea's unique topography, the ganglion cells are displaced laterally from their cone inputs, enabling separation of visual stimuli (left) and calcium imaging (right).

Connectomics

Serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBFSEM) slices through a volume of neural tissue, acquiring high-resolution (5 nm/pixel) EM images of each section. The resulting volume enables reconstructing neural circuits and their synaptic contacts in 3D, providing a comprehensive account of each ganglion cell type's upstream circuitry.

Our goal is to establish a feedback loop between physiology and anatomy, using connectomics to guide physiological characterization of rarer ganglion cell types and to determine the origins of observed responses. Connectomics will also be used to obtain a detailed understanding of the remodeling that occurs after retrograde degeneration of the dominant ganglion cell type following V1 damage.

ON (green) and OFF (magenta) midget bipolar cells traced from the major dendrite to the synapses within a cone pedicle.